Lithium Ion Like Battery with 3X the Energy Density, Sodium Glass Electrolyte

March 1st, 2017Disclosure: I sell solar power systems in New Zealand.

—

I’ll reiterate the usual warning when posting about battery technology “breakthroughs.”

Laboratory experiments have virtually nothing to do with finished products that you and I can buy. Indeed, DO NOT hold your breath waiting for this. That said, it’s VERY interesting, if you’re like me and follow energy storage news daily.

If you want a minimum ten year, non toxic battery based on sodium today, Aquion is it. However, Aquion technology is big and heavy—it’s for fixed energy storage applications only.

The researchers below are trying to get rid of the big and heavy characteristics.

I’ll post the entire piece below, as stories like this have a tendency to quietly disappear.

One other thing:

This research is supported by UT Austin, but there are no grants associated with this work.

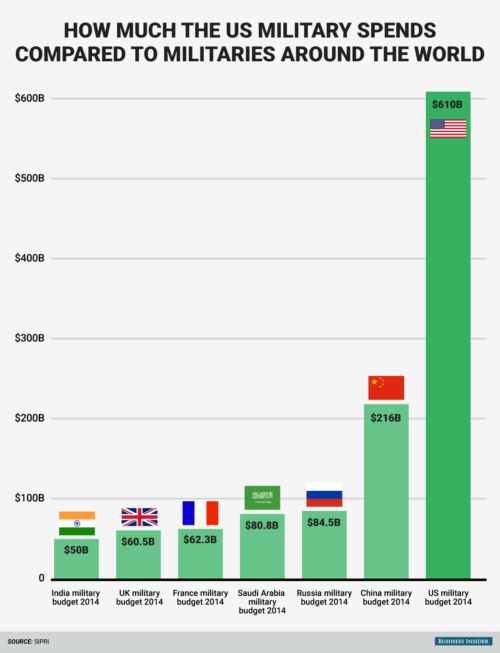

Fascinating. Here’s the chart from, Trump Seeks U.S. Military Spending Boost, Domestic Cuts:

You know, because…

Via: The University of Texas at Austin:

Feb. 28, 2017

AUSTIN, Texas — A team of engineers led by 94-year-old John Goodenough, professor in the Cockrell School of Engineering at The University of Texas at Austin and co-inventor of the lithium-ion battery, has developed the first all-solid-state battery cells that could lead to safer, faster-charging, longer-lasting rechargeable batteries for handheld mobile devices, electric cars and stationary energy storage.

Goodenough’s latest breakthrough, completed with Cockrell School senior research fellow Maria Helena Braga, is a low-cost all-solid-state battery that is noncombustible and has a long cycle life (battery life) with a high volumetric energy density and fast rates of charge and discharge. The engineers describe their new technology in a recent paper published in the journal Energy & Environmental Science.

“Cost, safety, energy density, rates of charge and discharge and cycle life are critical for battery-driven cars to be more widely adopted. We believe our discovery solves many of the problems that are inherent in today’s batteries,” Goodenough said.

The researchers demonstrated that their new battery cells have at least three times as much energy density as today’s lithium-ion batteries. A battery cell’s energy density gives an electric vehicle its driving range, so a higher energy density means that a car can drive more miles between charges. The UT Austin battery formulation also allows for a greater number of charging and discharging cycles, which equates to longer-lasting batteries, as well as a faster rate of recharge (minutes rather than hours).

Today’s lithium-ion batteries use liquid electrolytes to transport the lithium ions between the anode (the negative side of the battery) and the cathode (the positive side of the battery). If a battery cell is charged too quickly, it can cause dendrites or “metal whiskers” to form and cross through the liquid electrolytes, causing a short circuit that can lead to explosions and fires. Instead of liquid electrolytes, the researchers rely on glass electrolytes that enable the use of an alkali-metal anode without the formation of dendrites.

The use of an alkali-metal anode (lithium, sodium or potassium) — which isn’t possible with conventional batteries — increases the energy density of a cathode and delivers a long cycle life. In experiments, the researchers’ cells have demonstrated more than 1,200 cycles with low cell resistance.

Additionally, because the solid-glass electrolytes can operate, or have high conductivity, at -20 degrees Celsius, this type of battery in a car could perform well in subzero degree weather. This is the first all-solid-state battery cell that can operate under 60 degree Celsius.

Braga began developing solid-glass electrolytes with colleagues while she was at the University of Porto in Portugal. About two years ago, she began collaborating with Goodenough and researcher Andrew J. Murchison at UT Austin. Braga said that Goodenough brought an understanding of the composition and properties of the solid-glass electrolytes that resulted in a new version of the electrolytes that is now patented through the UT Austin Office of Technology Commercialization.

The engineers’ glass electrolytes allow them to plate and strip alkali metals on both the cathode and the anode side without dendrites, which simplifies battery cell fabrication.

Another advantage is that the battery cells can be made from earth-friendly materials.

“The glass electrolytes allow for the substitution of low-cost sodium for lithium. Sodium is extracted from seawater that is widely available,” Braga said.

Goodenough and Braga are continuing to advance their battery-related research and are working on several patents. In the short term, they hope to work with battery makers to develop and test their new materials in electric vehicles and energy storage devices.

This research is supported by UT Austin, but there are no grants associated with this work. The UT Austin Office of Technology Commercialization is actively negotiating license agreements with multiple companies engaged in a variety of battery-related industry segments.